The impact of lower Russian piped gas supply to Europe on the global LNG market

The European Commission has published an action plan to reduce Russian gas imports by two-thirds by the end of 2022. They propose to enable this by increasing LNG and other piped gas imports, increasing biomethane production and reducing demand by about 38 Bcm, mainly by substituting gas in power with wind & solar. It will be very challenging to align all the seven key components in this plan but the greatest challenge may be enabling contractually a two thirds reduction in Russian supply.

Most of the Russian gas is supplied under take-or-pay contracts and these do not provide an option for such a dramatic reduction in supply. It could only be achieved by the EU embargoing that amount of Russian gas or by persuading buyers to dramatically cut back nominations (find some way of declaring force majeure). Political opinion is divided about the need/desirability of such an approach and such drastic steps currently look unlikely.

We have modelled a number of scenarios including one where there is a complete cessation of Russian piped gas supply to Europe, but our base case assumes that Russian piped gas supply is not sanctioned or cut back by Russia. Instead, Russian supply falls because term contracts are not renewed. This could reduce the call on Russia to about 125 Bcm in 2023 and 100 Bcm by 2030 (from 142 Bcm in 2021). Domestic production continues to decrease (Groningen production ceases) as does demand. Surprisingly, this is a relatively well supplied scenario so it unlikely that governments will feel it necessary to introduce new regulations to restrict demand. European gas demand in Q1 22 is reported to have been 7% lower than Q1 21. Part of this can be attributed to a milder winter but the bulk of the reduction can be attributed to higher prices. The Dutch TTF averaged US$32.5/MMBtu over Q1 22 versus US$6.6/MMBtu for Q1 21.

[1] For the purpose of this blog, Europe is deemed to be the EU 27 plus UK.

There is very limited potential to increase other piped gas supplies as most pipelines are already operating close to capacity.

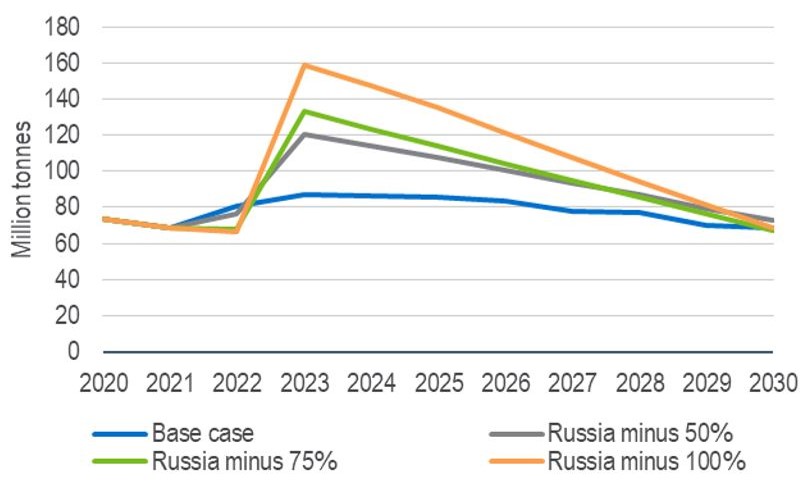

Our base case shows a relatively modest increase in LNG imports from about 69 million tonnes in 2021 to about 87 million tonnes in 2023,2024 & 2025, slightly less than the 89 million tonnes imported in 2019.

Our other scenarios assume a cut in Russian supply. We therefore modelled a 50% reduction, a 75% reduction and a 100% reduction. The call on LNG increases in each scenario with 121 million tonnes required in 2023 under the 50% cut scenario and a peak of 159 million tonnes required in 2023 under the zero Russian supply scenario.

Europe - call on LNG

NexantECA World Gas Model

Source: NexantECA World Gas Model

Is 159 million tonnes of LNG available? Can Europe absorb 159 million tonnes?

Europe currently has 248 Bcm (182 million tonnes) of LNG receiving capacity in its terminals with 209 Bcm (154 million tonnes) in the EU-27 plus UK. A complication is that 30% of that is in the Iberian Peninsula and very little of the LNG received in Spain can be piped to France, and on to other EU markets. Excluding Iberia, the EU currently has about 94 Bcm of terminal capacity, or 142 Bcm (104 million tonnes) if the UK is included.

The Gate terminal in Rotterdam has stated that it could expand capacity from 12 Bcm/annum to 20 Bcm/annum in 2022 and there are plans to lease an FSRU that could add a further 4 Bcm of capacity. The French government has tasked TotalEnergies with finding an FSRU for Le Havre and Italy is also seeking two small FSRU’s. Germany has chartered four FSRU that could collectively provide about 36 Bcm (26 million tonnes) of capacity. Thus, potentially by 2024, Europe could have 185 Bcm (136 million tonnes) of terminal capacity, or 253 Bcm (186 million tonnes) if Iberian capacity is included. In practice it likely to be much higher as recent events have shown that many terminals are able to operate well above their nameplate capacity.

Thus, Europe should be able to absorb 159 million tonnes of LNG.

Sourcing the LNG will however be more challenging.

[2]For the purpose of these scenarios, we have assumed the cuts are made in 2023 and are then permanent.

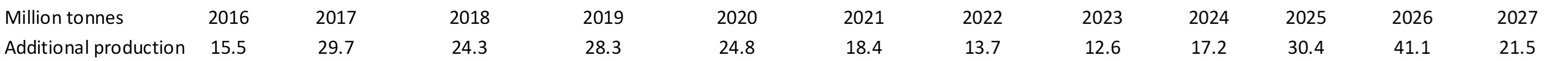

The LNG market is already very tight. About 383 million tonnes of LNG was produced in 2021 and this figure will only increase fairly modestly in 2022. Between 2016 and 2020 an average of 25 million tonnes of new production came on stream each year. However, that is likely to be closer to 14 million tonnes in 2022 and 13 million tonnes in 2023.

Lower Russian piped gas supply to Europe on the global LNG market

Hammerfest LNG and Prelude FLNG are expected to resume production in Q2 22 and may contribute an additional 4 million tonnes in 2022. Other producers may also be able to raise production levels slightly and collectively this this may result in 2022 LNG production being about 20 million tonnes higher than 2021. There is limited potential to squeeze more out of the system, but this should be enough to ensure that European demand in our base case is met (86 million tonnes in 2023, 2024 & 2025).

Under the scenario where Russian supply was cut by 50%, Europe’s LNG demand could increase to 121 million tonnes in 2023 an increase of 52 million tonnes over 2021 imports. This could just about be met but only by diverting about 19 million tonnes of existing production from other markets (assuming new supply can be directed to Europe). This should be manageable during a period of suppressed demand (it’s about 7% of the volume that went to Asia in 2021) as long as we don’t have a particularly cold 2022/23 winter. Chinese buyers are already reselling cargoes into Europe.

A 75% cut in Russian supply would be more difficult to manage. Under this scenario, Europe would need to import 133 million tonnes of LNG in 2023, almost double the volume imported in 2021. 133 million tonnes is not readily available. To hit this target, about 32 million tonnes of existing LNG production would have to be diverted from other markets. This could be challenging. It is the equivalent to a 12% cut in the supply to the other markets in 2021 and it is probably unrealistic to assume all other buyers will be happy to forego this amount, particularly during peak demand seasons. They are unlikely to voluntarily give up this amount and there is not currently a system in place that could enforce rationing (for instance, forcing producers to cut back supply into term contracts and releasing volume for supply to Europe).

Under the 100% cut scenario, Europe would need to import about 159 million tonnes of LNG in 2023. This looks to be an impossible target – unless there was massive restructuring of the global LNG market.

LNG is not required to replace Russian gas supply on a tonne for tonne basis. Some of the Russian supply will be replaced by additional supply from the other piped gas suppliers and additional bio-gas & bio-methane production. Gas demand will fall as more renewables contribute to power generation and high prices accelerate demand destruction.

Gas demand falls in all of our scenarios, but it falls at a different rate in each scenario. More modestly in the base case but accelerating in subsequent cases as governments/regulators introduce measures to dampen demand. This could range from mandating lower thermostat settings for heating buildings, increased subsidies on solar rooftop and heat pump installations, to rationing of gas supply to industry.

Governments will need to be pulling every lever of control at their disposal if they see a high likelihood that we may move into the -75% or -100% scenarios.

Inevitably there will be more coal fired power generation but coal for gas substitution may only be necessary in the relatively short term and may not impact long term plans to phase out coal burn in power generation.

The European Commission has proposed to present a legislative proposal on a minimum gas storage obligation. Member States will be required to ensure that the underground gas storage infrastructures in its territory are filled up to at least 80% of their capacity by 1 November 2022, rising to 90% for the following years. This is not quite as dramatic as it may sound as the 90% target reflects average historic EU storage filling levels (with an average of 87% in the last few years) and it should be possible to meet these targets under our base case. However, under the other scenarios, where the shortage of gas is more acute, this becomes much more challenging. Member states may have had to move to the “just in time” model with less emphasis on diverting gas into storage.

Prices will remain high. The UK NBP averaged US$40.90/MMBtu in March 2022 compared with US$6.20/MMBtu in March 2021 (Dutch TTF US$42.22/MMBtu versus US$6.15/MMBtu). In all of our scenarios, prices remain high (circa US$25/MMBtu) for the next three to four years, as does volatility.

Running more coal fired power could be seen to suggest that emission reduction targets have been abandoned and energy transition plans compromised. However, this is unlikely to be the case as many of the supply mitigation steps being taken could have the effect of speeding up Europe’s energy transition to net zero.

Alternative piped gas supply. Europe’s other piped gas suppliers are unable to make up any Russian shortfall as supply is already fairly close to the maximum capacity of many of the relevant gas pipelines. The “Others” (Norway, Algeria, Libya and Azerbaijan) supplied 170 Bcm in 2021 and the EU has estimated that it might be possible to increase by 10 Bcm in 2022. However, this not sustainable as it can only be achieved by postponing maintenance on pipelines and production facilities. Significant increases will only be possible after investment. For instance, Azerbaijan could double its supply to Europe, but this would only be possible if the TAP pipeline was expanded to double its capacity.

There are no White Knights sitting in the wings who could quickly step up as piped gas suppliers. Turkmenistan (via Azerbaijan) and Iran (via Turkey) could enter but only after investment in pipelines/connectors.

This highlights the major challenge – investment. Significant increase in gas/LNG supply to Europe will only be possible after further investment in production facilities and infrastructure. Will suppliers be prepared to make these investments if there is a risk that when the new capacity comes online it immediately becomes a stranded asset as the need for the gas has waned?

What impact does all of this have on the global LNG market:

In our base case, very little. New European demand is largely offset by declines in demand in other markets.

In other scenarios, adequacy of LNG supply becomes an issue. In the 75% cut scenario European needs could only be met if LNG was rationed to other markets in order to release enough for Europe. At his point LNG market fundamentals come under severe stress (contracts, supply obligations).

High prices lead to demand destruction. China’s LNG imports in Q1 22 were 11% lower than Q1 21. India’s down 19% (Jan/Feb 22). This is not going to be a short-term issue as high prices are likely to be a feature of the market for some time to come. If lower prices return, we should not expect to quick rebound to earlier demand levels. Much of the destroyed demand will be permanently lost.

Pre-conflict long-term LNG demand forecasts now look far too optimistic, a greater focus in Europe on a move away from gas will eventuate. Some emerging markets may not come up to expectations as LNG is leapfrogged by alternatives.

In all of the tested scenarios the period of high LNG demand in Europe is relatively short lived. Demand peaks in 2023 or 2024 and then rapidly declines so that in all scenarios, 2030 imports are down to 2020 levels.

Recent events have galvanised the developers of new liquefaction projects in the USA and they are now rushing their projects to FID. However, these facilities will not be online for three to five years and therefore will not be able to meet Europe’s immediate needs. They will come online when European demand could be waning. If global demand has not picked up substantially by then, the industry may move back into a period of overcapacity (and lower prices).

Irrational exuberance now, looks to be feeding the next wave of a supercycle later in the decade

Whilst the leasing of four FSRU’s for use at German ports is justified the construction of three onshore LNG terminals at these ports remains difficult to justify.

Our scenarios (and most other reviews) have not considered a reduction in Russian LNG exports. Russia exported about 28 million tonnes in 2021 (from Yamal and Sakhalin LNG) and this constituted about 7.5% of global supply. Exports are expected to double by 2026 after Ust Luga and Arctic 2 LNG come online, and Russia’s market share to increase to about 11.5%.

The loss of all or part of Russian LNG supply will have a significant effect on the market and will make it even more difficult to supply additional LNG to Europe. If this happens it is likely to galvanise actions to reduce demand and bring Turkmen and Iranian gas to Europe.

Find out more...

Keep updated with latest developments in the natural gas/LNG industry by subscribing to NexantECA's World Gas Model.

The Author

Tony Regan, Lead Gas & LNG, Asia Pacific